- Sit down, please.

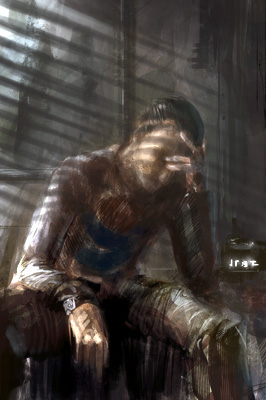

He's sitting on his bed, head in hands. All bravado has gone out of him. His hands, now rubbing his eyes, don't feel like they belong to him anymore. They feel like ghosts, attached to him by some strange mechanism he has no control over.

He doesn't want to look up, because he'll see the pictures on the walls – of loved ones lost, of glories past – and he will remember how alone he is. There's a certificate there, too, somewhere, for working in deep-space environments. He worked as a miner on asteroids, an incredibly dangerous task that paid well. The men in his family worked in the same way, and most of them have died. He's the last one, of the men, of the family, of everything. And soon, he’ll be gone as well.

And yet ... and yet he knows that it doesn't matter, if he'll only allow his grief to fall away like the old skin it is. He doesn't want to take his mind off it, because that'll only mean he's running away. Instead, he focuses; he gazes inward with a burning stare, willing himself to look his fate directly in the eye. He doesn't blink. He doesn't blink.

After a while, he feels something give way under the force of his stare, and his mood shifts from victimization to purpose. He accepts the joke of life. He feels the sorrow lift from him. He begins to feel that nothing is impossible.

He starts browsing through pamphlets.

Instant response to most of them is to toss them in the garbage. There's nothing they can do for him that'll change things, nothing they can tell him that he doesn't already know.

When he gets to the card from the Sisters, he almost throws it away like everything else. Then he notices what the card actually says.

The card has a phone number, and below that, the line, "This is not what you think."

He frowns, and calls the number. When a voice answers, it asks him how he got the contact info.

He's silent for a little while. The voice waits patiently. Then he starts telling it who he is and what has happened.

The voice came from a TV box. There was an avatar on the screen: his AI doctor. You didn't get a human doctor unless you were a pilot, or willing to pay an exorbitant fee.

- We've received the results of the blood test, the voice said. The avatar moved its lips in sync with the words, and didn't smile. That's when he knew it was serious.

He meets the Sister at a café. Over a cup of tea, she makes him an offer.

"The doctors are reliable," she says, stirring the tea with a spoon that she then sets aside. "They only give that card to people whose entire profiles - psych, medical, economy, everything - match what we're looking for. So we know you're right for us."

"And now I need to know whether you're right for me," he replies, and sips his coffee.

"Precisely," she says, and pulls out some boxes from her bag. They're each the size of a fist, identical, made of marble. "What I'm about to tell you might sound incredible," she continues, "but you'll need to take a lot of things on faith from now on. There are forces in this universe. Some of them good, some evil. Occult, even. And one of those forces, an evil one, is attempting to disrupt various spiritual lines, to influence the world in various ways. The Sisters have set up a task force to uproot it."

He stares her directly in the eye. "I don't believe you," he says. "Actually, I think you're crazy, and those boxes probably contain the eyeballs of your past victims or something."

She suppresses a grin and orders the boxes in front of him, three in a line. "Pick one."

He does. She opens it. The box contains a small marble, purple and opaque. The instant he sees it, he's flooded with a sense of well-being. Worries melt away, acceptance and joy light up inside of him, and the future, bleak as it is, seems like the best thing that could happen to him.

She closes the box, and the feeling fades away. She opens the other two boxes; they're empty.

"Very few people respond," she says. "But I saw that you did. You're attuned to them, which means you can find them."

"What do you want me to do?" he asks.

"Look away," she says. He does, and hears her re-order the boxes. Eventually he looks back, points at one box, and it contains the marble. They do this several times, and he always picks the right box. Every time it's opened, it makes him feel alive and happy. Yet when it's closed he doesn't need more; he's content with that brief glimpse. He mentions this to the Sister, and she nods, clearly pleased.

"I don't know what you saw," she says, "because it's different for everyone. I see snowflakes, gently drifting about inside the boxes. Other people see colours, and others can only tell by feel. Your mind picks whatever you can handle.

"I want you to leave your life," she says. "Come with us. Help put things right. There aren't many people who can do what we're asking you to do."

He's still not sure. Then again, he thinks, what does he have to lose?

- The results are not good. I'm sorry, the AI said.

He knew it wasn't sorry, that it was a liar. But he'd known that for a while now, and he accepted its preprogrammed response as a small comfort.

He's aboard the Sisters' ship. They're in high sec space, scanning for something. He's started to feel the pangs of impatience but he pushes them down. It's true that he doesn't have any time to waste, but all that means is that a second spent on aggravation is a second wasted. He looks around, tries to take everything in as if for the first time. The metal walls and railings, the lights in the ceiling, the muted greys and greens worn by people around him. It's all rather low-key and subdued, and yet it's perfect, if only because it is.

There's a shout, and the crew erupts in cheers. They've found a marker.

He sat there stunned as the AI told him he had somewhere between six and eighteen standard months to live. It was nothing they could prevent; at some point the brain would simply stop sending the commands for lungs to inflate and heart to contract. His mind would decide it was time to stop. There had been some limited experiments with automatic equipment, a type of pacemaker, but in order for it to work he couldn't exert himself under any circumstance, nor meditate or relax. Never drink, never do anything that might cause any sort of deviation from the norm. Never watch movies, never fall in love. Nothing.

- It's a choice between living and dying, the AI said, and he understood.

The ship destroys every pirate it finds at the location, and its sensors pick up a trail. The Sister in charge, the same one who recruited him, is very pleased. "It's not always that we find it," she says, "and even then, we have no idea whether it'll lead us to the right spot."

They move on.

- There is a chance you might live longer. The six to eighteen months is a mean time; there is nothing except the basic laws of probability that says you couldn't live a full life.

He thought about this.

- So I might die in ten years? he asked.

- Yes.

- Or I might die tomorrow, he said.

- Yes.

The AI watched him for a moment, then said, but chances are it will be within a year and a half.

He didn't ask how many had lived past that. He didn't want to know.

They've been through two more encounters. At least they've been lucky enough to find trails leading them deeper in. The Sister told him that sometimes the trail would grow cold and they'd have to go back to square one.

They're chatting busily while strapped into their seats, waiting for the pilot to finish off the last pirate. Remaining unfettered in the middle of combat is just asking for a broken neck. The crew members to either side of him are arguing about whether this is the second or third encounter, one claiming that the first one shouldn't count, the other that it should. It's an utterly pointless argument, and he understands it so well. Anything to keep their minds off the fact that they could die at any moment, either burned to a crisp or flash-frozen in space, their eyes bursting out of their heads.

There is a resounding boom as the last pirate is blown to shreds, then silence.

Speakers crackle. "This is it, folks. We've found the trail again, and this time it looks like the mother lode."

With bated breaths, they course toward their fate.

And then, with no forewarning, he started to laugh.

The AI was flummoxed.

- Do you need me to turn off for a moment?

- No, he said, still laughing.

He knew it wasn't shock, at least not completely. It was acceptance, and it had hit him like a hammer.

- Everything is clear now, he said. All the rules have been changed. The grand joke has come to its punchline at last.

The AI remained silent, though he didn't know if it was out of respect for the dead, or merely because it had no routines to deal with this sort of reaction.

- Everything is clear, he repeated. I only had one relative, you know.

- I know, said the AI.

- My grandmother. She died last year. I always admired her strength, her will to live in the moment, the simplicity she saw in things. I always tried to pare down my life to match that, cutting away the complexities. But that's just not something you can do. You can't ignore everything and force yourself to think simple.

He was babbling now, but he couldn't imagine stopping.

- True simplicity and purity of purpose comes only when you've faced all the complexities, and lived through them long enough – and deep enough – that you come through them, as if breaking through a barrier, and right out the other side.

- And you've broken through a barrier? the AI asked.

- I have now. You achieve simplicity not by keeping complexity away, but by embracing it, gladly giving yourself over to the torrents of life, and, laughing, realizing that it's all insignificant and that it holds no power over you, that life is one big joke with our death as the punchline and that no matter whether you find the joke funny or not it'll still be spoken right to the end, and that is the heart of humour and joy.

He stopped, almost gasping for breath. The AI stared at him.

- Would you like some pamphlets? it said at last.

"Deploy! Deploy! Go, go, go!"

They pour out, like blood spurting from a wound. Drones whizz past them in a battle frenzy. The pilot is keeping the pirates busy, keeping all attention focused on him.

They were all hand-picked by Sisters operatives. Every one of them immediately zeroes in on the same broken-down husk. It looks the same as the myriad other wrecks floating about, but they know better.

He's the first to reach it. It wouldn't show up on any scanner, that much is certain. It's a spherical thing, purple and opaque like the marble he saw, and surprisingly inert. Even when it's unconnected to anything, it doesn't seem to want to move. It takes three of them to pry it loose, and when they do, it feels like taking a splinter out of bare skin, like removing a thorn from the Lord's eye.

The sphere calls to him, but the happiness it promises is laced with confusion, and he senses undercurrents of doubt and madness. He ignores its call the best he can, and focuses on getting the thing back to the ship. The Sisters have told him that the sphere will be purified.

Instinctively, he knows that the item's placement here was intended to call hapless travelers, make this place into a death trap. But there's more at play than that. It feels like they've stumbled onto a dark tapestry, and managed to cut away one of the threads.

He looks at his hands. They're shaking from the strain of removing the sphere. And they feel a part of him now.

Inside his suit, he smiles.

He accepted the pamphlets with good grace, got up, and walked quietly out of the office, heading towards his life.

Nale's story continues in the Black Mountain chronicle series.