I'll likely never know which one of us was the traitor; the old man I destroyed, or me.

We all pooled into the classroom. I couldn't help but wonder why there was such a rush to get in when the same people couldn't wait to get out.

M. Cromwell came in a little later. Most teachers hang out in the classroom between sessions, like it's their own little fortress of knowledge, but he takes every chance to leave the room. He's probably smoking, but that's not the point. He gets a kind of begrudging respect from his students for this, like he's one-upping our own tardiness and lack of interest, and if you look at it with the right mind-set it makes you feel like he's one of us, dragged into that late adulthood despite his fervent protestations. I think that's horseshit. He just doesn't like us, that's all.

We were supposed to go over the basics of ancient Caldari history, which was an irony and a half since we're at war with them in the present. I'd imagined that the school authorities would cut this class from the schedule once the war started, but apparently the Gallentean educational establishment prides itself on not bending to the whims of pressure groups. As an idea, it sounded akin to a building trying not to bend to the whims of the bomb in its basement, but there we had it.

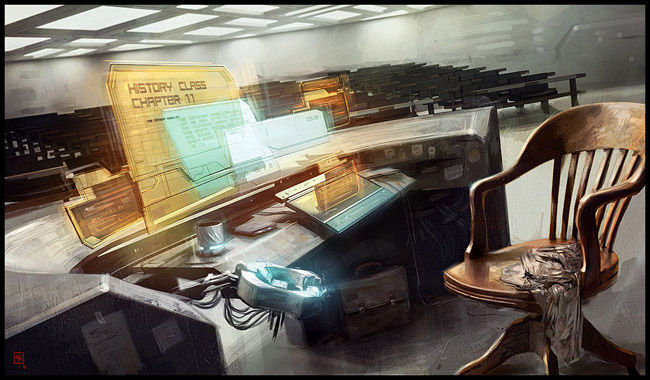

Cromwell was cranky from the word go. He walked into the classroom, smelling too strongly of fresh mint, and put his oversized coffee mug on his desk. The room was practically antiquated – most historians seemed to like them that way – but Mr. Cromwell had made a valiant concession to modern times with that mug, one of those self-heating motion refilter units that keep its drink permanently fresh.

"Alright," he said to the room, all of us already seated, "move in, come on. We don't have all day in here, you know." He hovered his finger over the vidscreen inset in his table, and the lights in the room dimmed slightly, counterbalanced by the glare from our own monitors.

"Where had we got to?" he said to the empty air. "Ah. Yes. Now." He looked up from the screen and directly at us. The man had taught this stuff for longer than I'd been alive, and you could see him slipping into gear. "The Cathura rebellion was, let me see, started exactly two hundred years after the Raata empire was formed and ended two years later, which puts it at 17670 and 72 CE, and if you ask me what that was in Yoiul years I'm throwing you out the window. The peace treaty they eventually signed was at the hall of…"

He paused and threw a quick glance at his screen, presumably to check that he was telling the same truths as usual - whenever old teachers do this I imagine an old man walking up a flight of stairs, brushing the handrail to ground himself - but when he caught what the text was saying, he sputtered and ground to a halt.

"I don't believe this," he said.

Twenty odd pairs of ears perked up.

"They've changed it. Again. Oh, for the love of ... alright. Look here," he said to us, and there was rancor in his voice, as if we were to blame for whatever had annoyed him, "the Current History section may have opened their arses to propaganda, but the Ancient one doesn't usually merit the attention of the secret police. This, you will be interested to know, is because we've taught it for so long that it's become ingrained in the minds of people who are now working adults, and as it turns out, altering the facts that we're now teaching to their children aggravates them far more than the lies they're fed on the nightly news. I guess their history lessons form an important part of every man's childhood, for which you have my undying pity and commiseration.

"Be that as it may, I would like you to ignore the wording of the key phrases you see on your screens. The treaty of Cathura was peaceably signed, with everyone behaving as gentlemen so far as the circumstances allowed. Its terms were not 'barbarous' as the text would have you think, nor were there 'sweeping' losses for one side as a result. Some people died of starvation, but it wasn't because their leaders were broke or powerless. The other side had slashed-and-burned as it went. You'll find this to be a common tactic in warfare anywhere in New Eden."

He read on for a silent minute, with quiet mutterings of "good lord" and "are you serious?" Eventually he turned back to us and said, "This is called loaded language, and the reason it's called loaded is because someone is holding a gun, aimed right at the writer's head if I'm any judge."

He paused, gently running his fingers over the vidscreen like a parent touching its injured child. "They can't change history, but slight adjustments of tone are allowed," he added with acid bitterness. "But we'll work on that. Two minute break, so rest your fragile young minds. I'm going to upload additional study material from my own collection."

There was a muted collective groan and a whispered few "not more texts, come on," but he ignored it. So did I. I was getting increasingly angry at the man.

It was that motion; the way he'd absent-mindedly touched the screen. As with everything else he did it spoke of a private love between him and old history, not a public one a teacher should share with his students. There are some people whose antagonism is merely an expression of affection coupled with a kind of innate cynicism. You get the feeling they want the best for you in a world that's going all to hell, even if they think your idiocy is contributing to the problem. They care for you despite your glaring faults. This is the only true love that exists, you might say. In my anger I saw him like an empty husk, loveless and grey.

I'd raised my hand before I knew it.

He fixed me with a glare and said, "Yes." Not my name; just 'yes'.

"Should we be breaking away from the material?"

"Heaven help us if you escape the confines of your minds," he said. Some people in the class tittered.

"But the texts that are taught everywhere-"

"Look," he said. "The Caldari have ways that go back just as far as ours and are usually a damn sight more honorable. Having a shadow update to the history texts call them 'barbaric' is doing a disservice not only to their age-old culture but to our integrity in looking at the world. And by the way, my little mutton-heads, this goes for other empires as well. Some textbooks that you won't be seeing in my classroom claim the Amarr are nothing more than slave-driving zealots, old monsters gilding their fingers in the name of some wispy little ghost. In fact the Amarr are a deeply spiritual and misunderstood group of people who are trying to better the world in ways we Gallente completely fail to appreciate. The fact that they cock it up half the time and have the worst PR agency in history is beside the point. This, this, this," he said to me, emphasizing each word like a hammer, "is what you need to get into your head before we can let you out into the real world. Think for yourself. God help us if you can't even learn to do that."

I was fuming and said, "Which we do by having you teach your own private version of the past?"

He opened his mouth to respond, and I opened mine to outshout him, but a soft voice at the back of the hall cut through our words like a stone thrown through fog. It said, quite politely, "Why is this even an argument?" and it came from Sheeran Keil, one of the best students in the class, if not in the school. He was hard-working, soft-spoken and unfailingly polite, and illuminated in that halo of faint brilliance you see on the people you simply know are going to go far in life. He was a Jin-Mei, too.

M. Cromwell's gaze didn't waver. He merely turned his head, like a stone statue, until his eyes, staring straight ahead, found Sheeran.

With the unfaltering bravery of the dying, Sheeran pointed at his vidscreen and said, "This is what is being taught. This is what we are supposed to learn. This is what I am supposed to learn during the class. I would like to learn it, M. Cromwell."

"If you think, M. Keil, that the Caldari should be retroactively trampled, then that's your prerogative. Heaven save me from debating a civilization's merits with a scholar."

"I'll be happy to take on extra studies-"

"That's not the point, M. Keil," the teacher said, an evil grin on his face. "The point is that you are here to learn, for it is by learning history, and indeed as is so often said, learning from history's mistakes, that we stand any hope of avoiding them in these new and treacherous times. If we paint the Caldari with the blackest of brushes we reduce them to crude caricatures, unworthy of our sympathy or understanding. Believe me, in a war, that is not the attitude you want to have."

"M. Cromwell," Sheeran said with an audacity even I found amazing, "in a war, I would have thought that was exactly the right attitude to have."

"Look, you guys had your chance and blew it," the teacher said to him. "You may think the Caldari should go the same way and simply surrender to the unstoppable might of the Gallente Federation."

It was a vicious insult to Sheeran's ancestry, and he made to defend it, but Cromwell silenced him by saying, "Stop nattering about the ones who dared fight back. All in class, now, sit up! The books are long since updated, so we will continue with the lesson as I intend to teach it." He gave me a final glare, then launched back into the books.

What I should have said was this:

I had just about had my fill of him, of his bullying others and hiding behind history. No one else was teaching so belligerently, and how could you believe the message, enticing as it might be, if the messenger himself couldn't be trusted? He might have a problem with revisionists, but he was teaching his own version of history, the one he'd formed in his own mind after all those years, instead of following the common consensus. He was bullying the learning into us. Anyone who dared think otherwise apparently deserved nothing but scorn.

I said nothing, and the class ran till completion.

Afterwards, talking to my classmates, I found that some people liked this little guerilla line he'd taken - the same who usually liked his brazen attitude - but others hated it. And in a strange and rather unpleasant way, I felt like I should have belonged to his supporters, because it's always good to feel like you've sided not only with the truth but the stamped-down truth, allied with the rebels and the real heroes the world is trying to silence.

But what we had, when you looked at it with honesty, was one man's interpretation of the truth, and whatever bravery he was instilling in us by his defense of history was discounted by his acts in class, which were teaching us the value of tyranny.

I dithered, and realized that I really wanted him to fail, to say something that would remove him from my world.

When he passed us, I walked behind him and quietly said, "M. Cromwell."

He did not stop, but slowed enough for me to catch up. "What do you want?" he said.

"So who are the good guys?" I asked.

It was a dangerous question, and he knew it, and I wanted him so badly to give the wrong answer. Instead he said, "People are people, with good and bad sides. Good people can do terrible things; bad people can perform wonders."

He left, and I let him go.

An idea began to form in my head, but I wasn't sure whether I could go ahead with it. So I followed Cromwell to the teacher's lounge, in the hope that I could talk to him for a little longer and make up my mind, one way or another.

When I got there the door was ajar, so I waited outside and listened. Cromwell was talking to a fellow teacher about the recent class, and I heard him say, "I think of it as charity work, really."

"Oh?" the other man said.

"If I don't raise their IQs by a few points, they might eventually forget how to breathe."

Stones in the fog. Stamped-down stones in the fog.

I didn't think about it for another second. I walked away, skipped the rest of my classes and headed off-campus, towards downtown. I spoke to authorities in one of the new institutions Mentas Blaque had set up, where I told them the easily verifiable fact that my teacher had gone against curriculum that might be politically sensitive, and the unverifiable lie that when asked who the good guys were, he had answered 'Caldari' without missing a beat.

M. Cromwell did not come to class the next morning.